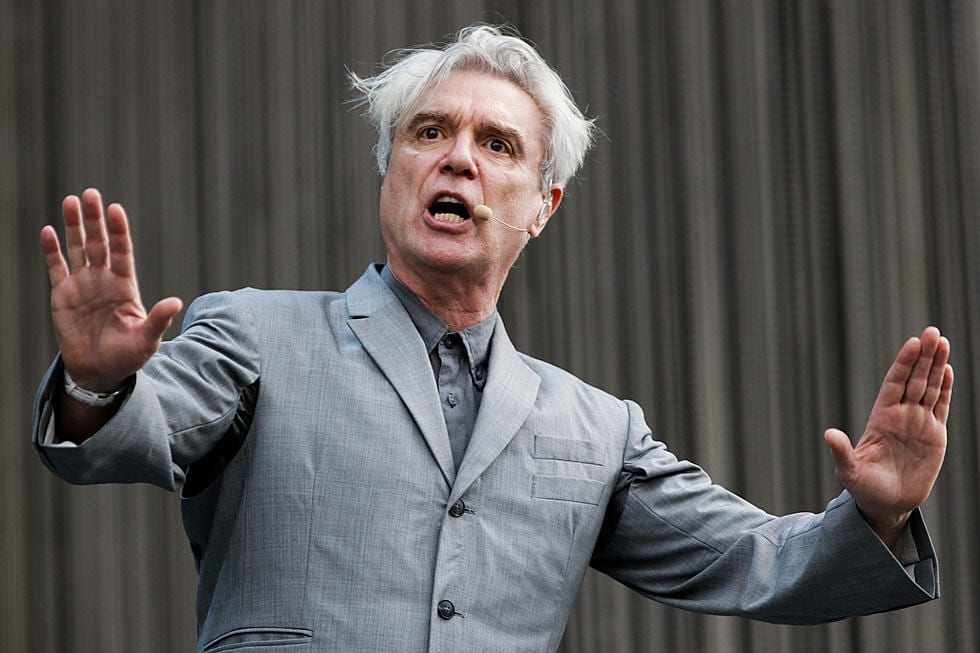

David Byrne: The Echo Chamber

Renaissance man David Byrne asks whether social media is actually narrowing our view of the world.

The Echo Chamber

Not too long ago some friends were asking each other, “How are Trump supporters so seemingly unaware of his lies and bullshit, and the ridiculousness of many of his positions and ideas?” (His claim that he “watched in Jersey City, New Jersey, where thousands and thousands of people were cheering” on 9/11 comes immediately to mind.) Lately it seems that anything that contradicts a passionate belief has become invisible.

The avoidance of a “reality-based community”—as the Bush advisors derisively called it—is truly puzzling, but the other reasons why folks are drawn to Trump and others like him are, in my opinion, pretty clear. One reason why folks on either side of the party line are angry with how things stand is that both sides sense that Congress is beholden to the money of special interests and consequently the voice of the people goes unheard. Democrats might blame the Koch brothers and I’m sure that conservatives blame some outside influences, too. The decision to bailout the banks doesn’t sit right with some, and others feel that the government wants to regulate their private lives.

The article “Why are Americans so angry?” from the BBC provides “five reasons why some voters feel the American dream is in tatters”: the economy, immigration, Washington, America’s place in the world, and existing as a divided nation. And here is a link to the the Pew Research Center article, “Beyond Distrust: How Americans View Their Government”, from which a lot of the figures in the BBC article were taken.

According to a study by Nobel Laureate Angus Deaton and Anne Case, white middle class men may be killing themselves due to an increase in pessimistic outlooks concerning their financial futures. My guess is that the middle class senses the end of the American dream and that white middle class Americans are experiencing a lack of mobility and opportunity in the economic spheres where they were previously the privileged and entitled majority.

Americans feel disenfranchised—that the government isn’t responsible to the people and instead only responds to the wishes of special interests. In my opinion, the latter is not just a feeling, it’s true. Add to that the feeling of impotence—that traditional remedies and corrections aren’t effective anymore—and you have a pretty explosive cocktail. This probably drives a lot of Sanders supporters, too, though my bias leads me to assume that Sanders isn’t propagating outright lies and misconceptions—he’s actually addressing issues and not simply massaging his ego and building his brand.

That anger explains a lot, but the question still remains: how do folks continue to ignore facts? How have people’s viewpoints become so insular and isolated that any contradictory information never even penetrates the bubble? How did we get to a point where dialogue is impossible? And I’m not just referring to this presidential race, but to many other areas of discussion as well. Am I imagining this or has the echo chamber, where one only hears what one agrees with, expanded in scope and at the same time had the effect of increasing that anger and the inability to have a dialogue?

It’s been suggested that social media has a big hand in this increase in insularity. By its nature, a social network is adept at creating in-groups that share similar likes and opinions. Like many people nowadays, followers of Trump (and other candidates) often get their news from social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook—which allows users to post articles and video from other sources. (TV is a big source of information, too, but then folks still gravitate to shows that project familiar and agreeable point of views.) The problem with Facebook and Twitter is that those platforms mostly present a point of view that you already agree with, since you only see what your “friends” are sharing. We all do this to some extent—your friends share news with you and presumably many of your friends share your viewpoints. The algorithms built into those social networks are designed to reinforce this natural human tendency and expand upon it—if you like this, you’ll like this. The networks reinforce your existing point of view in order to give you more of what you like, as that will make you happy and keep you on the network—and, in turn, more ads can be accurately targeted your way. You remain blissfully happy “knowing” or, rather, believing, more and more about less and less. Add that algorithm to folks’ natural inclination to seek points of view that confirm existing biases and you’ve got a potent combination. Once you’ve surrounded yourself with only one point of view, soon that point of view is all you hear.

That is why, a friend argued, Trump supporters are immune to criticism and to the exposure of his lies and false accusations: for the most part these algorithms and subsequent self-censorship make it so that they never see anything but what they already agree with. As often happens when groups of like-minded individuals discuss something, the result is that their points of view are not only reinforced but also become more extreme. Cass Sunstein describes this phenomena in his article, “Deliberative Trouble? Why Groups Go to Extremes”:

Like-minded people engaged in discussion with one another may lead each other in the direction of error and falsehood, simply because of the limited argument pool and the operation of social influences. … The point also bears on the design of deliberating courts, legislatures, and regulatory agencies. Above all, an understanding of group polarization helps explain why like-minded people, engaged in deliberation with one another, sometimes go to astonishing extremes and commit criminal or even violent acts.

This is a natural human tendency, and social media seems to encourage it. By design. In order to keep the eyeballs happy and people on the site, the news is filtered—you get fed content on subjects and people you have previously expressed interest in. The algorithm uses that information to find more articles, images, etc., that pander to your likes. You are an increasingly happier viewer as you see more of what you like.

Below is a selection from an article in The Guardian by Iran’s “blogfather”, Hossein Derakhshan. His blogging was, some years ago, very effective as a voice of protest and resistance—so much so that he was imprisoned for six years and only recently released. But now he senses that the web landscape has changed and voices like his don’t penetrate as much:

Instagram – owned by Facebook – doesn’t allow its audiences to leave whatsoever. You can put up a web address alongside your photos, but it won’t go anywhere. Lots of people start their daily online routine in these cul-de-sacs of social media, and their journeys end there. Many don’t even realise they are using the internet’s infrastructure when they like an Instagram photograph or leave a comment on a friend’s Facebook video. It’s just an app. But hyperlinks aren’t just the skeleton of the web: they are its eyes, a path to its soul. And a blind webpage, one without hyperlinks, can’t look or gaze at another webpage – and this has serious consequences for the dynamics of power on the web.

Wael Ghonim, who is credited with helping to launch 2011’s Tahrir Square revolution via his anonymous Facebook page, laments the state of things today via the New York Times article “Social Media: Destroyer or Creator?”:

We tend to only communicate with people that we agree with, and thanks to social media, we can mute, un-follow and block everybody else. Five years ago, I said, “If you want to liberate society, all you need is the Internet”. Today I believe if we want to liberate society, we first need to liberate the Internet.

We would like to think of the web at a place of pluralism—a place where many voices, often at odds with one another, can be heard. A place of diversity. A place to find out what wonderful and unexpected stuff exists that is different than anything and everything you already know. It seems that may have been true with net 1.0, but as market forces increasingly take effect, the diversity of voices, while it still exists, is now so filtered and targeted that you may only hear echoes of what you already believe. It’s human tendency—further complicated by the fact that doing so funnels lots of advertising dollars into the pockets of big corporations.

Here’s a review in the New York Review of Books by Jacob Weisberg of some recent books on this and related phenomena. He writes:

Some of Silicon Valley’s most successful app designers are alumni of the Persuasive Technology Lab at Stanford, a branch of the university’s Human Sciences and Technologies Advanced Research Institute. B.J. Fogg calls the field he founded “captology,” a term derived from an acronym for “computers as persuasive technology.” It’s an apt name for the discipline of capturing people’s attention and making it hard for them to escape. Fogg’s behavior model involves building habits through the use of what he calls “hot triggers,” like the links and photos in Facebook’s newsfeed, made up largely of posts by one’s Facebook friends.

A successful app, [Nir Eyal] writes, creates a “persistent routine” or behavioral loop. The app both triggers a need and provides the momentary solution to it. “Feelings of boredom, loneliness, frustration, confusion, and indecisiveness often instigate a slight pain or irritation and prompt an almost instantaneous and often mindless action to quell the negative sensation,” he writes. “Gradually, these bonds cement into a habit as users turn to your product when experiencing certain internal triggers.”

Facebook’s trigger is FOMO, fear of missing out. The social network relieves this apprehension with feelings of connectedness and validation, allowing users to summon recognition. …checking in delivers a hit of dopamine to the brain, along with the craving for another hit. The designers are applying basic slot machine psychology. The variability of the “reward”—what you get when you check in—is crucial to the enthrallment.

ISIS and other radical organizations take advantage of this web-based phenomena as well. They too target folks’ passions—videogames, for example—and their frustrations. Many of their recruits were not previously angry or radical, but social media allows all sorts of entities—the good and the bad—to tap into our latent feelings. This article in Teen Vogue describes just how ISIS uses social media to recruit American teens.

So what can be done? The article “Terror on Twitter: How ISIS is taking war to social media—and social media is fighting back” outlines some ways of mitigating the attraction of terrorist websites and ISIS’s presence on the internet at large, including banning jihadist content and ISIS users, counter-recruiting via target advertising and hackathons, and gathering counter-intelligence from the outside and in.

But that’s just focusing on ISIS. What about local politics? Aren’t issues of race and immigration similarly ramping up in the U.S. (and elsewhere) into intolerant screaming matches? How do you encourage tolerance and open-mindedness while promoting exposure to diversity of opinion? It’s an old question… As Alexander Hamilton wrote in The Federalist Papers of 1788, “The differences of opinion, and the jarring of parties…often promote deliberation and circumspection, and serve to check excesses in the majority.” Further to that point, from philosopher John Rawls:

In everyday life the exchange of opinion with others checks our partiality and widens our perspective; we are made to see things from their standpoint and the limits of our vision are brought home to us. … The benefits from discussion lie in the fact that even representative legislators are limited in knowledge and the ability to reason. No one of them knows everything the others know, or can make all the same inferences that they can draw in concert. Discussion is a way of combining information and enlarging the range of arguments.

Easy for Hamilton and Rawls to say, and for Sunstein to advise similarly as to group decision making (i.e., allow for dissenting views, limit the power of the leader, etc.). But what about in our day-to-day lives? What about the folks who will never hear that Trump is full of shit when he says he self-finances his campaign? See no evil hear no evil.

I’m probably as guilty as anyone, though I do scan about four to five different news sources during my daily browsing. While none of them are presented to me via a social media feed, the newspapers themselves are skewing more and more towards likable headlines, topics and subjects. Am I then supposed to force myself to read the Post and watch Bill O’Reilly from time to time?

Seriously though, some of those news outlets do skew towards opinions that are not reinforcing my pre-existing beliefs (the Financial Times, for example). So perhaps I have tempered some of my knee jerk reactions in some issues. But still.

I’m going to suggest that cycling or walking around in different neighborhoods gives one a slightly more face-to-face view of the diversity of humanity, especially here in New York. I love writing songs from different characters’ points of view—characters who are often saying things I would never personally say, but whose shoes I can put myself, sometimes.

Like most people, I gravitate to others who probably share many of my viewpoints… but not always. If it’s not already been filtered and combed through, sometimes we discover that friends hold some surprising viewpoints. And because they’re friends—or at least because I respect them—I’ll take those ideas on board, for a little while at least.

DB

New York City